2026 REGULATIONS EXPLAINED: All you need to know about F1's new aerodynamics

F1 goes into the 2026 season with an entirely new chassis philosophy. The cars will be lighter, more nimble, and better able to overtake… but what does it all really mean for racing?

Every few seasons, Formula 1 hits the reset button. While minor tweaks to the technical regulations are common between the seasons, sometimes a bigger change is required, and the rules of F1 are rewritten in a more substantial way. When this happens, we’ll get a new engine formula, or perhaps a new aerodynamic concept. 2026 is unusual in that we’re having both at the same time.

‘Unusual’ really doesn’t do it justice. It’s unprecedented – but it’s being done for a very good reason. F1’s power units are having their first major refresh for a dozen years, and there will be a new aerodynamic concept to complement them, which leads to a shake up of the pecking order with everyone starting from scratch.

It’s also a car designed to be safer – because F1 never misses an opportunity to use the experience gained over the last few years to build something stronger and better able to deal with whatever situations it encounters.

It is a lot of change, and the new and the novel tend to swamp everyone in jargon, but Formula 1 will still be delivering heart-in-the-mouth action… just maybe a bit more of it.

Will the cars look different?

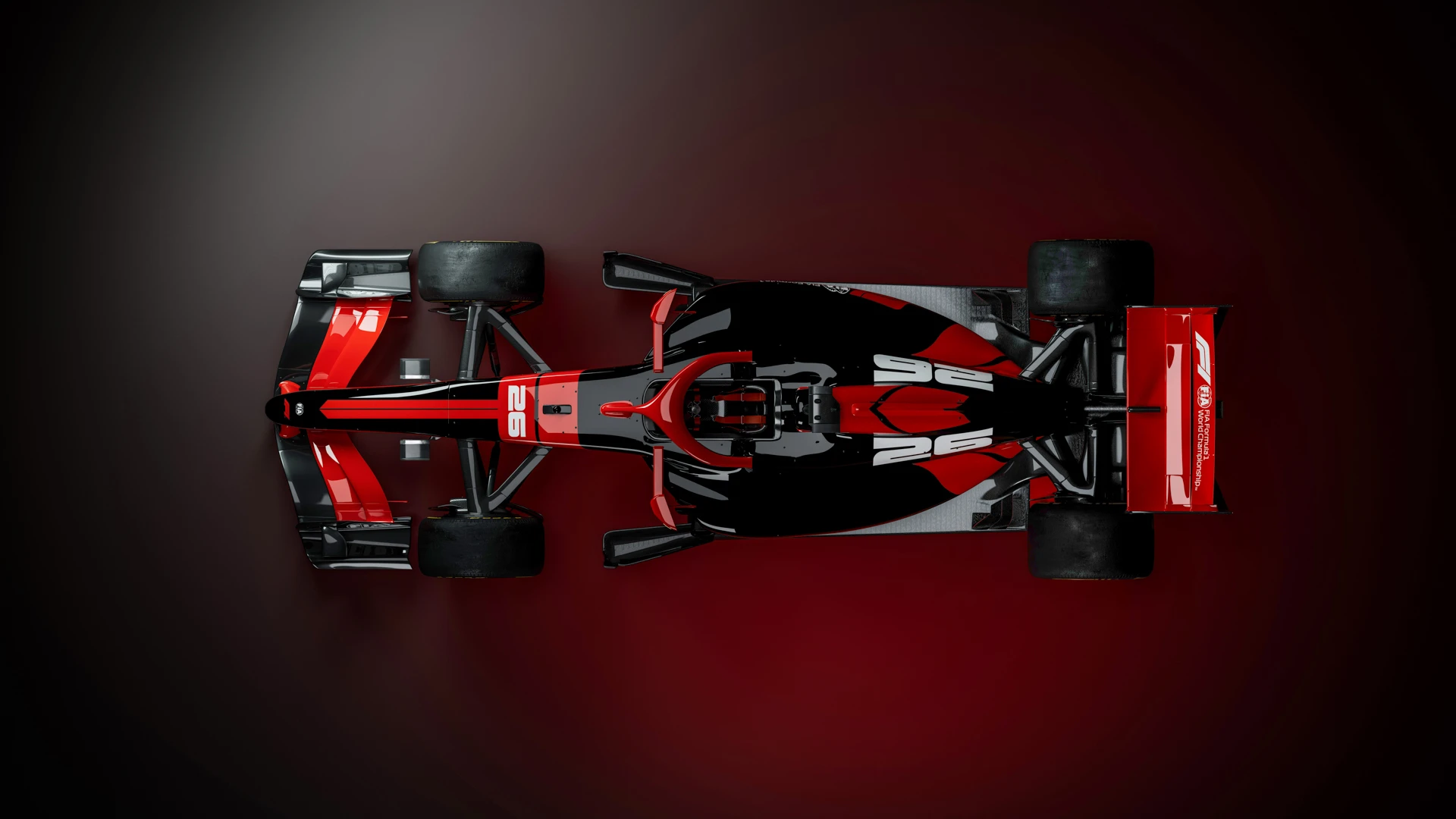

They will look different – but the sort of different that tends to get forgotten after a few months of the new season.

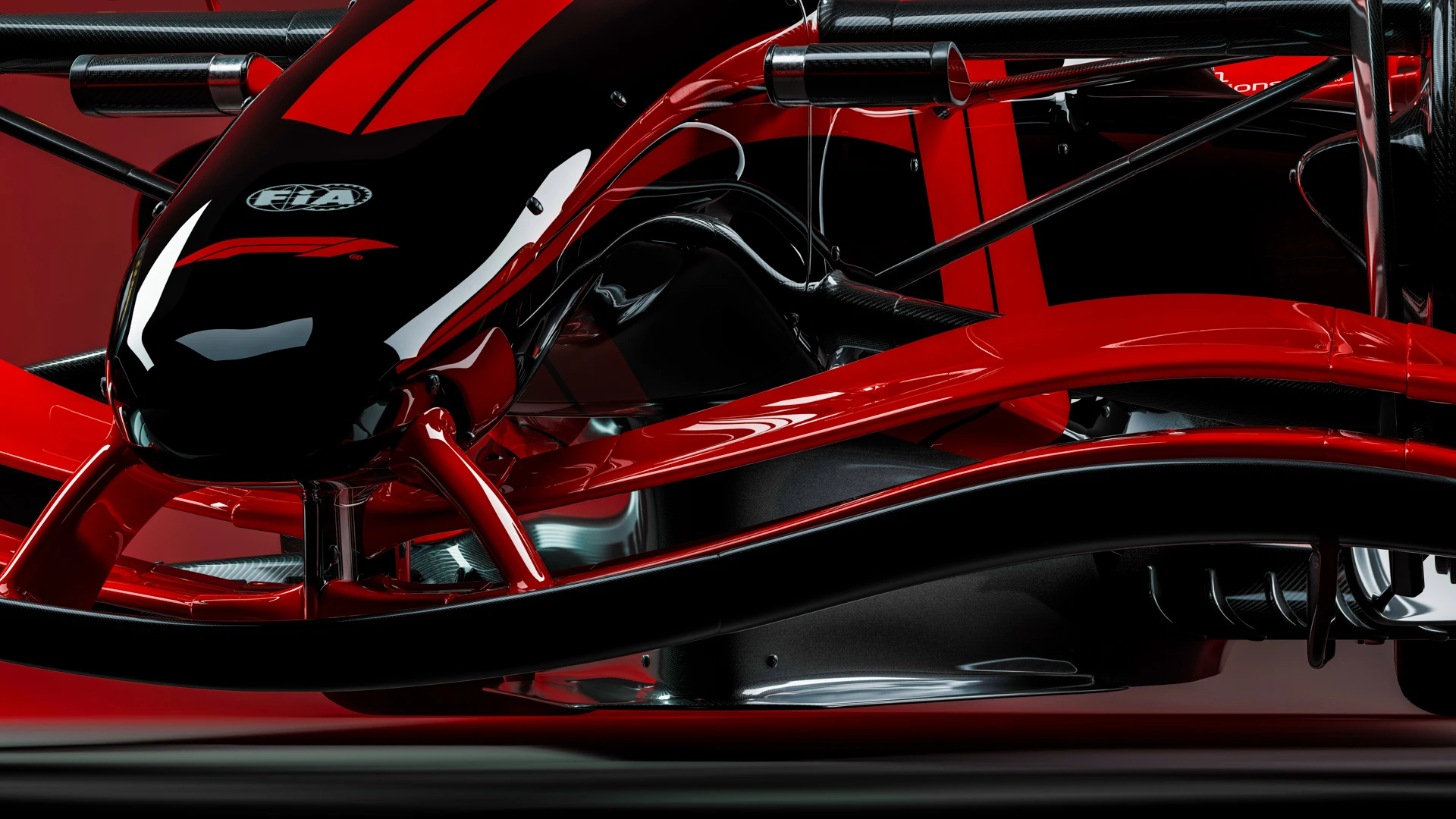

The main points to notice are that the front wing is simplified with fewer elements (the razor-like blade cascade) but more detail around the endplates. The ‘eyebrow’ winglets above the front wheels are gone, and there are bargeboards behind the front wheels.

At the rear of the car, the beam wings (that sit below the exhaust) are gone. Less noticeable – but perhaps of greater importance – the underside of the car is very, very different. The ground-effect generating Venturi tunnels carved through the floor are gone, replaced with a flat(ter) design, and a much larger diffuser at the rear of the car.

Does removing the tunnels mean the ground-effect era is over?

Yes. The tunnels under the car encouraged high-speed airflow, which in turn generates a huge amount of grip by sucking the car down to the surface. These forces don’t disappear with a flat floor but they are greatly diminished, and these new cars will be finding downforce in other areas.

The ground-effect era succeeded in many of its aims but as the teams developed their cars and recaptured more of their out-washing characteristics (more on that below), it got harder and harder to get close to the car in front. The new regs should promote closer racing.

How does the shape of the car promote closer racing?

Glad you asked! The front wheels of an F1 car punch a big hole in the air and create a lot of turbulence. Turbulence is the enemy of good aerodynamic performance. Generations of F1 designers have sought to push that turbulent air out to the sides of the car – outwash – which allows smoother air to infill and make the aerodynamic surfaces wrapping the rest of the car work much more effectively.

The problem with out-washing is that it creates a mass of roiling turbulent air behind the car, making it very difficult for a following car to stay close. These regs, mandating simpler front wings and in-washing bargeboards, are a robust solution designed to prevent out-washing.

We hear the car is to be lighter and more nimble. How? And why?

The minimum weight of an F1 car has been steadily creeping up, adding around 200kg over the last 20 years. More safety features and ferocious crash tests, combined with the extra weight of hybrid systems, have pushed it ever higher. It’s created a situation where the cars were very fast, very safe… but not quite as nimble as their predecessors.

So, for this year, the size of the cars has been reduced, with a wheelbase (the distance between the two axles) that is 200mm shorter, and a floor that is 100mm narrower. The tyres are also slimmer, with the tread width reduced by 25mm at the front and 30mm at the rear. Their total diameter also shrinks, by 15mm at the front and 30mm at the rear.

The regs reflect this, with the minimum weight reduced from 800kg to 768kg. There’s no guarantee the teams will be able to reach that minimum – indeed, reducing weight is expected to be one of the key engineering challenges.

Does this mean the car is less safe?

No. None of the crash tests have been diluted. The cars will have to pass homologation tests at least as stringent as those faced last year. In several instances, however, the tests will be tougher.

There’s a new crash test for the roll hoop (the structure on top of the car), the load for which rises from 16g to 20g, while the nose cone now features a two-stage impact structure. This is to deal with the phenomenon of secondary impacts: it’s not uncommon to see the nose cone crumple as designed to absorb a heavy impact, but then continue to spin and have a secondary impact, with the crash structure already detached. The new version provides greater protection.

On the subject of the nose, the front wing now has an ‘active’ component. What’s active about it?

Both the front and rear wings have active – i.e. moveable – elements. These operate like a Venetian blind. When the blades are ‘closed’ they are providing downforce, but also creating a lot of drag. When they ‘open’, both drag and downforce are reduced.

It’s a best-of-both words situation: downforce for higher speeds through the corners (Corner Mode); reduced drag for higher speeds on the straights (Straight Mode).

Since 2011, the rear wing has had an active element within the Drag Reduction System (DRS). It’s use during a Grand Prix was restricted, only chasing cars within a second of the car in front were allowed to use it, and then only on specified straights. The new system is useable by all of the cars, all of the time.

The reason the front wing will now also realign, is to better trim the car and provide more stability, in harmony with the movement of the rear wing. It’s common to adjust the front wing manually, in the garage and during pit-stops, to better balance the car, and F1 tried a driver-adjustable front wing in 2009, without much success. This system will be automated, keyed to the engine maps.

Next Up

.webp)

/Bottas%20Cadillac%20seat%20fit.webp)

.webp)